Welcome to THE HARMONIES THAT ONCE SURROUNDED US: a history of human consciousness from a Western point-of-view. I truly hope you find the time you spend here worthwhile. However before you dive right in, and if you haven’t already done so, you might want to go to the ‘about’ directive at the top of the Home Page. The information you’ll find there will help you determine whether or not you want to stay; and if you do, what you might expect. Either way, may our alter-ego goddesses both go with you…

What say you and I conduct a little experiment in consciousness? Using our mind’s eye, let’s see if we can put ourselves back into that long forgotten moment when humans everywhere are still revering the Earth as a living Goddess, and honoring her fruitful generosity as befitting a Great Mother. We can do this you know. All it requires is a little imagination; and a willingness to temporarily suspend our 2500 year-old propensity to experience the world in a manner the philosopher Karl Jaspers has dubbed: “the subject/object split.”

So let’s start with a brief trial run. As you read the following italicized section, imagine that you’re actually part of what’s being described — as if you’re inside the story looking out, rather than outside looking in as one typically is when under the enchanting the spell of the split. And why am I asking you to do this?

Because one of my main intentions in this 3-Part essay is to help you see that the way in which your literacy-based Western education has set you up to experience yourself in-the-world isn’t a hardwired given, but a deeply-engrained habit. History demonstrates that the First People of the Earth didn’t experience the world as other than themselves in the way you and I have learned to do. And why do I think that understanding this difference is so important?

Well to put it bluntly, just take a look around. Do things here in the US and elsewhere seem to be getting better? Hardly. One important contributor to this, I believe, is our unconscious fealty to the all-pervasive psychology of the split. Despite its remarkable benefits, in-habiting the subject/object split is dis-connecting us from your own true natures, undermining the societal bonds that hold our communities together, and destroying the life-sustaining ecological balance of this fragile planet.

Wouldn’t you like to see a more hopeful future for yourself, the Earth, and all its creatures become a reality in your lifetime? Then in order for you to become, and help others become, the future human that such a change requires (see Part 3), you’ll first need to understand how human consciousness functioned prior to the split (see Part 1); and then when, why, and how the split became first the West’s, and eventually the world’s, dominant form of consciousness (see Part 2).

Are you game? If the answer is yes, then let’s proceed…

This solid rock you feel beneath your feet is our true Mother’s bone. The soil you so lovingly till is her flesh. The waterways that vivify the land are her lifeblood. An annual profusion of luxuriant greenery is her queenly attire; and rippling fields of wildflowers bejewel her. In Egypt they call her Isis; and In Mesopotamia, Gulu. The Romans know her as Ceres. And for the First People of Greece, her name is Demeter (pronounced Da-ME-ter).

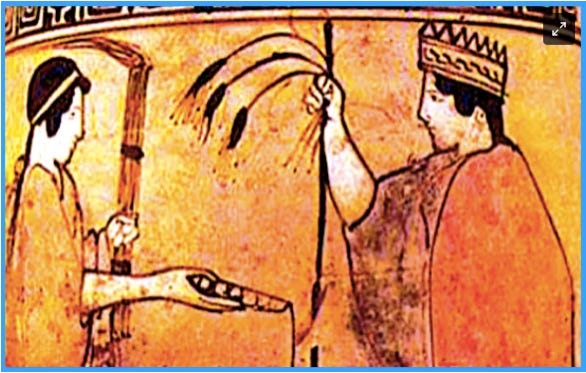

Often conflated with the primordial Earth-goddess Gaia, Demeter is the personification of feminine fertility. What truly sets her apart though is that she’s also the divine emissary of the plant realm and a spiritual liaison between human and plant consciousness. We Greeks are especially fond of her for bestowing on us two invaluable gifts: the life-sustaining practices of agriculture, and the life-transforming experiences of Mysteria — an initiatory rite-of-passage facilitated by a powerful plant-derived psychedelic.

In our everyday lives, we refer to Demeter simply as: The Mother. Especially endearing to our women is The Mother’s warmhearted relationship with her daughter Persephone, whom all speak of affectionately as: The Maiden. If you’re not already familiar with their story, here’s a brief to-the-point synopsis…

The goddess Demeter is raped by her brother Zeus; and in time gives birth to a daughter whom she mothers with great love and affection. Then one fateful day, Hades — Lord of the Dead, a second brother to Demeter, and Persephone’s uncle — abducts his young niece, and carries her down into the underworld against her will to be his queen.

As you might expect, Demeter is furious. So as retribution for turning a blind eye to their daughter’s rape and deeming it a ‘marriage’, but also for the trauma he had originally visited on her, Demeter turns Zeus’ delight, the beautiful verdant Earth, cold and barren. Then grief-stricken and despondent, she wanders the desolate countryside in search of her missing child.

All this time, in the Land of the Dead, Persephone is trying to come to terms with her fate. Being a queen definitely has its advantages; but being held prisoner is not OK. Most of all, she dearly misses her mother. So she asks her new ‘husband’ if she might visit Demeter in the Land of the Living. Realizing that Zeus is likely to compel his daughter’s wish whatever he does, Hades acquiesces. However as a parting gesture he gifts his young queen a ripe, red pomegranate.

Now Persephone knows full well that eating or drinking anything in the underworld will oblige her to remain there forever. Yet she goes ahead and sneaks six tiny seeds, thinking they won’t really count. Turns out she’s dead wrong.

Meanwhile, all this tumult has left Zeus in a quandary. How can he possibly placate his sister’s wrath, punish his brother’s chicanery, do right by his daughter, and rescue his beloved Earth — all at the same time? Seeing no other option, he declares that Persephone should spend half of each year with Demeter in the Land of the Living, and the other half (one month for each of those six tasty little seeds) with Hades in the Land of the Dead.

This is how the indigenous Greek mind explains the rhythmical oscillation of the annual vegetation cycle between the lush, fruitful warmth of summer and the cold, lean span of winter.

Why each September for 2000 years now, citizens of the Goddess-blessed village of Eleusis and our guests from all across the civilized world have been coming together to celebrate what the initiates of the sacred rite drink the perception-enhancing, reality-bending kykeon to brave: the terrible dark beauty of Persephone’s wedding night.

And why every year to this very day, when her annual finery is spent, Persephone must leave her devotees, her loving mother, and the welcoming Earth behind, and alone make the obligatory descent to the shadowy Land of the Dead and ‘the Dark One’ who ever so patiently waits…

“In the world of the dead there is no time. Yet every autumn, as the days grow shorter, the spirits of the underworld sense that Persephone must soon return. They grow restless and call to her with lost, hollow voices. In the world of the living, the sound of their cries becomes the sound of the wind sighing in the dry grass and moaning through the bare trees. For many of the living it is a sound that speaks to them of the frailty of life and the ultimate, unknowable void of death. They draw closer to the fire and to one another, and they cherish the warmth of life.” (Irene A. Faivre, “Persephone Remembers,” Parabola, Summer 1996.)

PERSONAL DREAMS & COMMON DREAMS

Now bring yourself back to the present moment. Well, how did you do? Were you able to get at least some sense of what the novelist L.P. Hartley was hinting at when he wrote: ”The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there?” If not, be patient. You’ll have more opportunities to practice shortly. It takes some effort to learn how to overcome the divisive psychology of the split. After all, as a child, it took you many years to learn how to perfect it.

So why am I so interested in this incestuous little tale of The Maiden & Her Mother? Because it’s more than just an old, old tale. Today we call such a popular, enduring story a ‘myth’ and regard it as imaginative fiction. However according to the 18th-century historian Giambattista Vico, the original meaning of the Greek word mythos was: ‘the true story’, not the false. So which is it: truth or fiction?

The psychologist Carl Jung thought it was a little of both. Like a dream, myth floats in the liminal space between conscious and unconscious, truth and fiction. The only difference is that dreams are uniquely personal and myths are collective. So let’s think of a myth then as a ‘common dream’ — one that arises spontaneously from the imagination of an entire people and gradually takes shape over the course of many generations. And just as personal dreams can at times play a compensatory role in one’s personal psyche by dramatizing problematical attitudes and situations that require our attention, common dreams do exactly the same for the collective psyche.

Rape seems to have been a recurrent theme in the common dreams of the First Greeks. Perhaps this was simple testimony to traumas unhealed and crimes unpunished. But when a difficult theme appears more than once in a dream or a myth, or in multiple related dreams or myths, then it’s likely that the psyche is attempting to come to terms with something pretty gnarly.

So with not just one rape but two, The Maiden & Her Mother had to have been trying to make a point; and I suspect that point may have been something more than simple compensation. What if this strange little story was also a well-camouflaged alternative history — perhaps crafted intentionally, perhaps spontaneous — of some very significant turn of events that couldn’t be spoken of openly without inviting reprisal?

The Greece our historians remember was a society of gods and men: a more patriarchal Greece. Could this poignant account of a mother/daughter relationship and the traumas they endured have been a clever way of preserving the memory of an older, more matriarchal Greece and its involuntary subjugation by a rising patriarchy? In other words: might the women of Late Neolithic Europe (ca.10,000-4,500 BCE) and their traditional matriarchal societies have experienced the slowly tightening grip of patriarchal dominance as the psychological and moral equivalent of rape?

I’ll let you judge for yourself once I’ve made my case. But for us to proceed, we first need to clarify what these terms ‘matriarchy’ and ‘patriarchy’ really mean. In today’s usage, both terms commonly denote contrasting ways of organizing society. But this sociological level of definition is contingent on a deeper psychological meaning.

When viewed as a functional psychology, the term ‘matriarchy’ means: a manner of being human in-the-world that reflects the values and priorities of a more feminine expression of consciousness. Chief amongst these is the importance of one’s familial commons, which includes not only the humans held close by biology and long association, but all sentient and insentient constituents of the natural world as well. In other words: the priorities of WE in its widest, most all-inclusive sense.

The term ‘patriarchy’ means: a manner of being human that reflects the values and priorities of a more masculine expression of consciousness. Patriarchal priorities center around the primacy of personal struggle, adventure, and accomplishment — ie., the priorities of ME in its narrowest, most exclusive sense.

However underpinning both the sociological and psychological levels is the even more fundamental level of consciousness itself. Because when we see matriarchy and patriarchy as differing but complimentary configurations of human consciousness, and observe the intertwined co-evolutionary nature of their temporal relationship, what we discover, what reveals itself so beautifully — because it’s the foundation of everything in the human experience of the phenomenal world — is an all-inclusive, still-unfolding, and as yet unfinished history of human consciousness.

THE PATRIARCHAL COUP

So what do I mean by “the intertwined co-evolutionary nature of their temporal relationship?” An epochal shift away from matriarchal and towards patriarchal dominance appears to have begun sometime around 10,000 BCE, and took some 5000 years to mature. So it was a gradual coup, a slow-motion transfer of power. Was this the one and only time such a shift had ever occurred? Or was this just the latest oscillation in a longer-standing cyclical dance?

Either way, this most recent shift to patriarchal dominance totally transformed the place of women in society; and not for the better. Like the proverbial frog in the pan of slowly heating water, no one seemed to notice just how draconian the process really was — to a degree that even the fact that things may have once been very different was totally erased from humankind’s Collective Memory.

Now I’m certainly not the first to champion the ‘matriarchal hypothesis’. It’s best known proponent to date has been the controversial archaeologist and anthropologist Marija Gimbutas. Her critics, however, argue that there just isn’t enough evidence to support the possibility of a pre-historic matriarchy. But again, what if this lack of evidence wasn’t accidental? What if the rising patriarchy was relentlessly astute at obliterating the matrifocal past?

We do know, for example, that during the Late Neolithic (ca. 6500-4500 BCE) Greek temples originally dedicated to goddesses were quietly re-dedicated to gods. No reasons were given, no justifications proffered; it was simply done. It’s also possible that at the same time certain compensatory common dreams — such as The Maiden & Her Mother — may have been ‘revised’ or sanitized to make the offending parties look good.

No version of the Persephone story I’ve read has ever used the word ‘rape’, or anything even close to it. I recall one patriarchal scholar even attempting to justify the rape by claiming that Persephone fell in love with her abuser because: “he treated her so well.” And I do find it telling, that when I search my online dictionary today for the meaning of the term re-matriation, what pops up instead is re-patriation!

One can catch a glimpse of the old matriarchal order being deposed in the history of European shamanism, because the Late Neolithic was also the time when males began to successfully usurp the traditionally feminine role of shaman and healer. And I find it truly ironic that the main weapon the patriarchy used to achieve gender and societal dominance was The Mother’s gift of the Agricultural Revolution.

”With the concentration of political power associated with the agricultural occupations, men sought and bequeathed the office [of shaman]. Rites increasingly became performances rather than egalitarian group activity. The pantheon of spirits, once accessible to all, became the shaman’s spirit helpers.” (Paul Shepard and Barry Sanders, The Sacred Paw, The Bear in Nature, Myth, and Literature 1992, brackets mine.)

Trauma workers tell us that victims of abuse have a tendency to themselves become perpetrators. However, I really doubt that the old matriarchs literally abused their men. Restrained, held them in check, yes; but maltreated them, no. Now I could be wrong about this, because Dr. Gabor Maté points out that trauma isn’t what happens to you, but what happens inside you in response to difficult external events. In other words: it’s possible that any restraint men experienced under the communal priorities of the matriarchy did inhibit their instinctual need for self-accomplishment.

And yet once the patriarchs had gained an upper hand, they sure behaved like they’d been abused! For example: during the Classical Period in Greece (4th and 5th centuries BCE), it was the women who were being restrained and relegated to 2nd-class status. And the classicist Norman O. Brown adds that by the 5th century the suppression of gender-equal rights in Athens had become a seriously volatile socio-political issue.

I do think it’s accurate to characterize the patriarchal Greek attitude towards women in general as largely one of distrust, perhaps even fear. This fact comes to light in another popular common dream: the tale of Jason and the Argonauts. The very first test the predominantly male crew of the Argo must pass on their initiatory journey to secure the Golden Fleece (i.e., the prize of masculine hegemony) is to escape from the clutches of a community of bloodthirsty women.

The Argo drops anchor at Lemnos, where the crew finds the isle in the possession of a remnant of the old matriarchy. The island’s seductive queen explains that the men of Lemnos have all abandoned them, and tries to persuade the Argonauts to stay. But the voyageurs high-tail it out of there once they discover the grisly truth that the men of Lemnos have all been ritually murdered — by their own wives, sisters, and daughters!

In addition to a compensatory function, there’s one other way in which personal and common dreams are similar. Both can be prophetic. On occasion I’ve had a dream that I didn’t immediately understand; but then the ensuing movement of my life would make its meaning crystal clear.

So I wonder: could a common dream of an earlier humanity ever contain a prophetic message for a future humanity? Say, for instance, a dream about the rapes of the Earth Mother and her daughter sent forward in time to help at the very moment when the patriarchal mindset is positioning itself like never before to have its way with Mother Earth? And if you think I’m exaggerating, consider for a moment the well-coordinated effort to deprive women of their bodily sovereignty ramping up right now across the US and elsewhere. And then consider the implications for the Earth of a newly-created financial instrument that Wall Street is currently trying to float dubbed a Natural Asset Company or NAC.

BREAKING YOUR WESTERN HABIT

Now that we’ve set the historical stage for our imaginal experiment, let’s take a moment and zoom out from all these patriarchal machinations so that we can better understand this idea that human consciousness has had as complex a history as Great Britain, or physics, or baseball.

A very disturbing trend has been stealing across the world for some time now, the consequences of which have become especially visible in the U.S. The customs, institutions, and resources that have traditionally belonged to everyone — long referred to as: ‘the commons’ — are increasingly being expropriated by private interests for their own personal benefit. Our own current president is an especially egregious example of this particular leaning.

“In his Farewell Address on January 14, 1981, President Jimmy Carter worried about the direction of the country. He noted that the American people had begun to lose faith in the government’s ability to deal with problems and were turning to “single-issue groups and special interest organizations to ensure that whatever else happens, our own personal views and our own private interests are protected.” This focus on individualism, he warned, distorts the nation’s purpose because “the national interest is not always the sum of all our single or special interests. We are all Americans together, and we must not forget that the common good is our common interest and our individual responsibility.” (Heather Cox-Richardson, “Letters from An American”, Substack, Dec 29, 2024.)

The problem here should be obvious: the less we hold in common, the more we divide and fragment. Thus the flag that too many of us in the US are flying these days is no longer the traditional stars and stripes; but as the writer Kurt Vonnegut would have it, a skull and crossbones emblazoned with the words: “Hell with you Jack I got mine!” This trend is being exacerbated by our historical allegiance to a politics that encourages ‘rugged individualism’, and our collective phobia around ‘creeping socialism’. Despite all the ‘Make America Great Again’ rhetoric, anyone not blinded by ideology can see that such a mindset cannot possibly make for a peaceful, enduring, sustainable society. So why has this become such a popular inclination?

I believe the answer lies in the exponential growth of the form of human consciousness I made reference to at the get-go: the ‘subject/object split’. Over the course of the last three millennia, the split has gradually become the West’s dominant paradigm. And now — thanks to the global success of its two most appealing expressions: the scientific method and the occidental model of education — the ‘Western form’ has gone on to achieve global dominance.

As a consequence, for the majority of us today the split is synonymous with consciousness itself. We ‘swim’ in its pervasive psychology like fish do in water; and we’re generally as unaware of it as the fish likely are of the water. On its upside, the split’s objectifying proclivities have been responsible for a number of humankind’s greatest achievements, including: philosophy, science, technology, all our humanities, and a good many of our arts.

But on its downside — what Jung would call it’s ‘shadow side’ — the split’s polarizing tendencies have been gradually and almost imperceptibly dis-connecting us each from the other, and all of us from the natural world. This last consequence — which essentially consists in the substitution of culture for nature — has now reached a point where we’re literally destroying our ability to sustain ongoing viability as a species. So where has all this left us?

The term ‘consciousness’ first came into popular usage in the West during the 17th century. Prior to that, the equivalent term was ‘human nature’; and the question that European philosophers and theologians had long been debating was: is ‘human nature’ (i.e., consciousness) fixed and constant in its expression, or can it change its form of expression?

For centuries now, the West’s preferred answer has been: fixed and constant. Perhaps the most relevant example of this is the materialist (or physicalist) argument by many contemporary philosophers and scientists that consciousness is exclusively a product of brain function. And what exactly are the characteristics of such an ‘epiphenomenal’ consciousness? Well, what a coincidence! They’re exactly the same as the core attributes of the subject/object split: an absence of emotion in problem solving, linear thinking, sustained attention span, and objective reasoning.

This odd fortuity raises two important questions. First: is the Physicalist explanation of consciousness settled theory; or is it actually just an unstudied assumption? What if it’s primarily an artifact of both philosophy and science as we know them today being children of the subject/object split; and therefore profoundly beholding to the split’s perceptual and cognitive biases? After all, most Western-trained thinkers have never experienced themselves and the world in any manner other than from the subject/object view-point.

And second: ever since the 1850’s, Western scientists have largely assumed that the Neanderthals were something they may not have been: brutish and stupid. So could consciousness be the new Neanderthal?

I ask this, because now in the 21st century, the fixity argument appears to have run its course. Emerging concepts such as neuroplasticity (i.e., the brain’s ability to construct new, or re-construct old, synaptic connections) are suggesting it too may not be true. If your brain is capable of re-wiring itself, then the structural ‘architecture’ of your consciousness as you know it is more likely to be just a deeply-engrained habit. And since habits can be broken, it would follow that the form of human consciousness can and does on occasion change.

A contemporary phenomenon called the “overview effect” is powerful evidence for this. Astronauts are returning from space awe-inspired. Seeing the Earth from space has not just inspired them, it has literally trans-form-ed their experience of consciousness. If every person on Earth today could do this , it would probably go a long ways toward antidoting all the tiresome bickering and squabbling. Unfortunately that’s not yet logistically possible.

But there is another kind of overview experience that is available to anyone who makes the effort. Because the most awe-inspiring and exquisitely beautiful understanding of our human possibility that we could ever hope to have, equal in its transformative power to the view of the Whole Earth from space, is the Big Picture history of humankind’s still-evolving experience of consciousness.

The Greek word historia originally meant: ‘a looking into’, or ‘narrative about’. A history of consciousness, however, is fundamentally different from the factual chronicle of events, ideas, and personalities that comprised the history you studied in school. Think of it this way: if consciousness were an animal, our conventional understanding of history would be the animal’s tracks. A history of consciousness is the animal itself.

Perhaps we should start paying less attention to those interesting tracks, and more to the phenomenon responsible for them. So instead of presenting you with another objective compilation of knowledge about consciousness, I want to focus on our subjective experience of this still-very-mysterious phenomenon.

Here’s an analogy to help you understand this important distinction. Studying the proliferating literature on psychedelics may prove quite informative; but it won’t trans-form you or your consciousness. However, should you have the desire and the opportunity to introduce one of these remarkable substances into your own bodily chemistry, and given a supportive set and setting, it just might do both.

So for our purposes here, let’s define ‘consciousness’ experientially as an individual or group’s qualitative manner of being human in-the-world. When treated as a subjective phenomenon, consciousness presents as an inseparable blend of content and form. Content is everything we’re sensing, thinking, feeling, or otherwise perceiving. It’s the attention-grabbing foreground of our experience. Form is the invisible background that organizes the ever-changing stream of content into a functional whole.

Content is uniquely individual. No other person has ever experienced the world in quite the same way as you do. Form is collective. Most members of your culture unconsciously participate in essentially the same form. If you’ve been educated in an alphabetically-literate Western culture, as anyone reading this essay probably has, then you’ve been primed to in-habit the ‘Western’ form. The problem is: if you remain unwittingly immersed in your conditioned form, then it’s almost impossible to see that other forms can and do exist. So to be able to experience a different form, you must break or step outside your Western habit.

There are many ways to do this. One is to immerse yourself in an indigenous or non-Western culture. A second is to make the ‘Journey to the East’ as the novelist Hermann Hesse illustrates so beautifully in Siddhartha, and as so many Western Buddhists are finding ways to do today. You can intentionally re-structure your patterns of perception and cognition with some skillful guidance and a compatible psychedelic. You can, as we’re doing here, use the history of consciousness to experience a ‘Journey to the Ancestors’. Or you can create your own unique way. It’s your choice.

So with all that said, are you ready to zoom back in and resume our imaginal experiment? This time, however, we need to go all the way back to the very beginning of the human odyssey…

IN THE EARLY MORNING OF THE WORLD

Imagine that you’ve just awakened from a fitful night’s sleep, and found yourself alone, in the dark, and hunkered down in some unknown forest. Your initial reaction is an understandable mix of curiosity and fear. However once you realize that danger isn’t imminent, you begin to gradually relax. That’s when you first notice the soft, plaintive call of your one seeming companion: a solitary night bird.

With first light you discover that you’re crouching on the bank of a slow-moving river, that makes a bend against some chalky cliffs at the base of a strangely familiar mountain peak. Mist curls off the river’s glassy green surface; and everywhere you look fish are rising. ”How beautiful, but how weird!” you think. “I could swear I’ve seen those cliffs and that mountain before. But when and where? It sure reminds me of the backdrop to that picturesque little Greek tourist town I passed through three summers ago. But there’s no town here; and looking around I see no signs whatsoever of human activity. Everything looks and feels totally pristine.”

As the day begins to slowly open out, necessity gets you up and moving. But there’s something very amiss with your body. It’s simply not working in the way you’re used to. “It’s like being in someone else’s skin. Seeing my reflection in a still pool of water, my face is darker and far more weathered. My vision is…well…that’s where things are getting really weird. I have no sense of perspective, no perception of depth or distance. Everything around me appears to be uniformly co-present, as if I were living in a huge flat-screen TV image. But perhaps the strangest thing of all is the sheer volume of multi-sensory information flooding my awareness.”

You may not know it, but the triune brain of this body you’re currently occupying is as fully developed as the modern brain you’re accustomed to. Both have exactly the same functional capacity for physical, emotional, and intellectual expression. The brain you’re familiar with is primarily utilizing its intellectual and emotional capacities to organize your experience. This older body’s brain is employing its sensory, instinctual, and emotional capacities. That’s why you’re experiencing such an extraordinary rush of sensory input. It feels like all the filters that modern life requires have been removed!

Wandering through the forest, you enter a leaf-hidden glade, and immediately spy a small deer grazing on a leafy shrub. You and the deer size each other up; and when you show no signs of being a threat, the demure little creature cautiously returns to its meal. It’s odd, but you definitely feel a kinship of sorts with this little guy. It’s as if you know exactly what she or he is thinking. But really it’s more how. Since the deer is thinking in the same sensation-bound manner you are.

“All my thoughts, and probably this deer’s as well, are being in-formed by the same five senses; and consist primarily of concrete pictures, smells, sounds, touches, and tastes rather than the musings, abstractions, and conceptualizations I normally experience as ‘thinking’. In fact, being in this older brain seems to allow no room whatsoever for the incessant stream of associative thoughts that my 21st-century brain normally entertains. That old 70’s catch-phrase: “be here now,” is suddenly making a lot more sense!

When the deer and I are sensing in the same way, and thinking in the same concrete manner, we’re functionally at-one. But this experience of perceptual and cognitive at-one-ment seems to be only a given when I’m in this older brain. When I’m in my 21st-century brain, intention and effort are required to make it true. My old-brain function brings the deer and I closer. My new-brain function turns the deer into an ‘other’ by erecting a formidable ontological barrier between myself and the deer.

So what about this whole forest then? Could it be ‘thinking’ in the same sensation-centered, concrete way as well? If so, what would constitute the forest’s sensorium? Might it be the sum total of all the information being gleaned by trees, plants, animals, and humans that participate in and comprise its extended body? And right now that definitely includes me.”

Then, in a flash, everything gels. “These two contrasting patterns of brain function are essentially responsible for two contrasting experiences of consciousness. For my newer brain, the forest is an interesting collection of ‘other-than-me’ phenomena. For my older brain the forest, the deer, and myself are all taking part — each in our own way — in one common ‘holomovement’.”

As the magnitude of this insight slowly sinks in, you think to yourself: “Now what was that old indigenous Guatemalan greeting: the one that always seemed a little TOO familiar?” Your eyes brighten, and a big smile crosses your face. You turn once again to face the still-quizzical deer. And throwing your arms wide so as to embrace the whole forest, you ebulliently exclaim: “Good to see your faces again. Good to see your mouths again. Good to smell your sweet, sweet breaths!”

THE ANIMAL AT-ONE-MENT

Once asked what she had learned from a lifetime spent amongst the orangutan communities of Borneo, the Primatologist Dr. Birute Mary Galdikas responded: “Serenity.” In one word Dr. Galdikas captured the essence of what it means to be on the Earth in the animal form of consciousness. That animals, plants, and other Earth-born life-forms participate in the phenomenon of consciousness in ways that can be both similar to and very different from humans is a possibility that many Westerners, including our philosophers and scientists, are only beginning to entertain.

For most of my adult life I’ve called the ponderosa-forested mountains of northern New Mexico home. Were I to select a word to describe what living encircled by these stately trees has taught me, I too might choose ‘serenity’. When first I arrived, I had it all wrong. Nature isn’t the competitive struggle my American culture had taught me it is. Rather it’s a complex symphony of integrated co-operation. Trees don’t hoard water or nutrients solely for their own benefit. They share them with each other through their root systems, and through the fungal networks that they live in continual chemical communication with. Above ground, each tree gives the impression that it’s a distinctly separate organism. But in the hidden world below, all are at-one.

The same holds true for our animal brothers and sisters. ‘Survival of the fittest’ doesn’t always mean that the fiercest competitors in the predation sweepstakes are the winners. That’s a capitalist fantasy. If it were true, predatory species would be committing suicide right and left by overexploiting their food sources; and they don’t do that. The prudent predator lives in a balanced equilibrium with its prey because collaborative inter-dependence, not unbridled self-interest, determines who’s actually nature’s fittest.

For the First People of the Earth, plants and animals never were ‘other’. They aren’t for most contemporary indigenous people either — that is unless, or until, one has been educationally entrained by the polarizing ontological assumptions of Western consciousness. The First People once did, and many still do, participate quite naturally in the animal and plant forms. And because of this ‘consciousness comm-union’, each species emanates from the wellspring of creation — which is to say each embodies its own characteristic form of one all-embracing consciousness field. So let’s dub this serene, un-self-conscious, instinctual harmony with each other and the Source: the Animal At-one-ment.

The panicked deer surrendering to the cougar’s bloody embrace. The great flocks of birds and schools of fish all wheeling about in perfect unison. The orca families of the Pacific Northwest, where “overt violence or aggressive behavior between individuals, even among males, has never been observed.” And wherein social interaction isn’t typified by Darwin’s tooth and claw, but by “co-operation, co-ordination, communication, trust and acceptance.”

Then some 6 million years ago our most distant hominin ancestors began the long slow journey up from and out of the animal realm. In the process they carried the Animal At-one-ment with them; and over time advanced it through at least 17 iterations. The last of these, some 300,000+ years ago, resulted in modern Homo sapiens. And somewhere in all of this — probably with the development of language-facilitated communication, estimates of which vary wildly from 70,000 years ago to several times that — the Animal At-one-ment morphed into the Human At-one-ment; and by so doing became the original form — the default setting — of human consciousness.

THE HUMAN AT-ONE-MENT

The First People’s at-one experience never was a consciously reasoned aspiration. It was a completely instinctual and totally unconscious given. Functionally it consisted in a mode of perception and cognition, with an ‘architecture’ and a set of ‘rules’ different from the mode you and I inhabit today. In other words: the At-one-ment was simply the way the First People were human in-their-world.

Surely life for them had to have been, in its own way, as difficult and challenging as it is for us. They obviously had to deal with all the aspects of life and death that we do. “We eat to be eaten,” is how one spiritual teacher put it. But at the same time they had an easy, natural, unspoken connection to life and to each other that you and I today can only imagine. From a purely functional perspective, the original form was more closely related to what neuroscientists today call ‘primary consciousness’ — all involuntary and unconscious (autonomic) bodily systems — than to the thought-origination, cognition, and reason characteristic of what they call our more modern ‘secondary consciousness’.

I suspect that the original at-one form of consciousness was as fundamentally matriarchal (we) as our current Western form is fundamentally patriarchal (me). It has been demonstrated . A recent study suggests that human toddlers tend to behave pro-socially towards both humans and animals. The authors attribute this to budding altruism. I think it’s more likely a demonstration of ontogeny (individual development) recapitulating phylogeny (species development). Children today, as always, are being born into essentially the same experience of consciousness as animals and the First People; but then, right from the get-go, they get socially indoctrinated and ‘schooled’ out of it.

Now I probably don’t have to tell you that what I’m outlining for you isn’t a widely embraced way of looking at things. In fact, neither of the two main competing hypotheses of human origins would be likely to concur with my evolutionary take on the progression from animal to human consciousness. Mainstream anthropologists and academics certainly wouldn’t, since a majority still generally assume that one’s form of consciousness is neurologically determined. In other words: in their view human consciousness changes quantitatively as society evolves and people learn from their experience; but it doesn’t change qualitatively — except in very minor ways.

But I have three good reasons for championing such a qualitative, consciousness-centered, developmental narrative. First, I find the possibility of an organic, ‘home-grown’ evolutionary scenario more plausible than a model that is hinged on outside intervention. Plants, animals, and humans are all children of Mother Earth. I don’t think we need intervention to explain the evolution of advanced civilization, even if its rise and fall has taken place more than once. The answer, I believe, lies in our psychology, not in our DNA.

Second, the etymology of languages that descend directly from those of the First People appears to support the likelihood of an earlier, more unified form of human consciousness. In the mother tongue of the Tzʼutujil Maya, for example, which is a derivative of the 5000-year old ‘Proto-Mayan’, there’s no verb ‘to be’. So the only way one can say “I am,” or “I exist,” is to name to whom or to what I belong or am at-one with.

And third, I respect and take very seriously the long view of history preserved in the collective memory and oral traditions of the world’s indigenous peoples. Here’s a very distilled, somewhat enigmatic, history of consciousness from the writings of the late Cheyenne linguist Dan Moonhawk Alford…

“Long ago, men, animals, spirits and plants all communicated in the same way. Then something happened. After that, we had to talk to each other in human speech. But we retained the ‘old language’ for dreams and for communicating with spirits and animals and plants.”

So what did happen? Why are we who we are now rather than who we were back then? Before we can answer either of these questions, we first need to understand what our term ‘consciousness’ actually meant for our most distant human ancestors. Plato says that all human knowing is remembering. I began this essay with the old, old story of The Maiden & Her Mother to purposefully jog your memory. It’s also why I asked you to imagine yourself — some spiritual traditions would say: ‘remember yourself’ — in that long-ago moment, rather than just reading about it as you normally would.

Imagination transcends space, nullifies time, and dissolves boundaries; and to understand the First People’s at-one form of consciousness we need to do all three. Sounds difficult; but really it’s not. It’s likely you’ve done it many times in the past while reading something that really interested you, something that literally ‘captured your imagination’. So what we’re doing here is turning that accidental occurrence into an intentional exercise, which is actually a powerful old Sufi practice that Jung re-dubbed: active imagination.

So now it’s time we leave the ‘early morning’ of the human world — ca. 300,000 BCE (the emergence of modern Homo sapiens) to ca. 3,000 BCE (the decline of the primal matriarchy); and move on to ‘late morning’ — ca. 3000 BCE (the consolidation of the patriarchy) to ca. 400 CE (the demise of the At-one-ment). If we zoom in on the very end of this ‘late AM’ period, we’ll we have much more to work with than primitive tools, artifacts, campgrounds, and burial sites. Because everything is about to, in a marvelous word coined by James Joyce: “wholyrolyover.”

“When Persephone hears the first, faint sighs of the dead in the cooling autumn winds, she is filled with dread. ‘They call to me. They call to me,’ she thinks as she gathers the harvest. ‘But how can I leave this life? It is too beautiful. The sky is too blue, the sun is too warm, the air is too sweet to leave behind. The spirits of the dead cannot understand. They are cold and remote. They have forgotten the beauty of life.’” (Irene A. Faivre, “Persephone Remembers,” Parabola, Summer 1996.)

HOLDING THE WHOLE WORLD TOGETHER

So now let’s you and I return, in imagination, to Greece — only this time its the beginning of the Common Era. Every autumn, for as long as anyone can remember, when the time comes for Persephone to return to the Land of the Dead, the Greeks throw her going-away parties in the guise of local harvest festivals. One of these humble beginnings has outstripped all others, and blossomed into Greece’s most beautiful, powerful, and influential spiritual tradition: the Eleusinian Mysteria.

The name Eleusis means: ‘place of birth’. The time-honored rite that’s still flourishing in this modest agricultural village is the last great societal institution of the Greek At-one-ment; but the end is fast approaching for both the At-one-ment and the rite. And the cause of both’s downfall is the best example I know of what Moonhawk was referring to in his enigmatic hint: “then something happened.”

The year is 364 CE. You and I have come to what today is modern Greece, but at the time was the Roman Province of Achaea. For three centuries now, the Greeks have been peaceful subjects of the Roman Empire; but trouble is brewing. Emperor Valentinian I has just issued a decree outlawing all nocturnal festivals — a blow aimed directly at the region's last surviving and most beloved Goddess shrine: the temple complex at Eleusis. News of this has traveled fast; and the Greek people are literally up in arms.

Inspired by the story of Persephone and Demeter, and observed each year in their honor, the Eleusinian rite has been a work-in-progress now for close to 2000 years. It originated sometime around 1500 BCE, when the Greeks were little more than a quarrelsome family of indigenous tribes. In the centuries that followed, the rite grew steadily in size, sophistication, and renown. But now it has become a round plug in a square hole. With roots deep in the old consciousness, the rite is a miniaturized version of the matriarchal At-one-ment struggling to survive in an increasingly unfriendly patriarchal environment.

By 500 BCE, when most of the other traditional goddess shrines had been re-dedicated to gods, the matrifocal observance at Eleusis each autumn was still attracting upwards of 40,000 celebrants from all across the civilized world. Now, some 900 years later, the rite remains a major institution of pan-Hellenic culture — even as it struggles with dwindling participation and increasing allegations of corruption.

Truth is, the we-oriented At-one-ment, which has been the rite’s psycho-spiritual foundation, is on its last legs. A new kind of human — predominantly male, patriarchal, and alphabetically-literate — is beginning to call the polis home. This new human is less tribal and more individualistic, less instinctual and more rationally astute, less sensually participatory and more intent on becoming self-aware through philosophical inquiry. Rumor has it that wealthy Athenians of this ilk are throwing parties where the rite’s fabled consciousness-enhancing kykeon is being illegally served, the carefully-guarded formula apparently procured through theft or bribery.

The village of Eleusis sits on a fertile agricultural plain, 22 kilometers west of Athens. It’s the place where Demeter, in her desperate wanderings in search of her missing daughter, is said to have first been treated kindly by humans. The Mother rewarded this kindness by gifting humanity the aforementioned practices of agriculture and the sacred rite — a natural symbiosis that explains the rite’s simple closing: “Rain, bring fruit,” a symbiosis that will continue to be remembered and honored long after the rite itself is gone. For example: a Brit named E.D. Clark will visit the ruined shrine in 1801 CE, and mention finding Persephone’s larger-than-life statue standing half-buried in a huge steaming pile of manure.

The Emperor Valentinian is a devout Christian — but a well-educated, pragmatic one. The uproar his decree is causing genuinely perturbs him; and so he turns to his trusted provincial Governor, Vettius Agorius Praetextatus, for counsel. “Should I back down, and allow Eleusis to remain a living hothouse of paganism? Or hold firm, and risk it becoming a nexus of insurgency against Roman occupation?”

The reported exchange between the Emperor and his Governor is a perfect cameo for what’s at stake in this pivotal moment. Valentinian no longer in-habits the old at-one form of consciousness. His literate urban education and religious indoctrination have made him a living embodiment of the new patriarchal form. Praetextatus, on the other hand, is not only a staunch pagan (from the Latin paganus, meaning: 'country boy’), but a veteran initiate of the Eleusinian rite. So like the rite, he too is still spiritually rooted in the increasingly anachronistic matriarchal At-one-ment.

“I think you’re making a grievous mistake,” warns the popular Governor of Achaea. “Not only is your decree fostering resentment and fomenting rebellion, it’s effectively making life unlivable for the Greek people.”

Praetextatus’ bold rebuke both agitates and perplexes the powerful Emperor of Rome. And just so you understand the risk the Governor is taking by speaking so forthrightly, when Plato spoke similarly to the Emperor Dionysus of Syracuse he narrowly escaped execution and was immediately sold into slavery.

Praetextatus concludes by distilling the Mysteria’s fundamental reason for being into six prescient words. And he does so not only for Valentinian’s benefit but for yours, mine, and all posterity’s — especially anyone who finds herself or himself psycho-spiritually dis-integrating, societally dis-connected, and at-one-ment deprived in this 21st century of the Common Era. It’s imperative that the Eleusinian tradition be allowed to continue, adjures the zealous Governor. And why? Because, in his own exact words, the annual celebration of the rite is what: “holds the whole human race together.”

BURIED IN THE BODY

In an earlier section, I helped you imagine yourself in-habiting the First People’s consciousness. Now let’s further expand our understanding of who they were, and how their normal, day-to-day consciousness differed from yours and mine.

The first Westerner to dig deep into this matter was an Italian historian named Giambattista Vico. In 1725 CE, Vico published his magnum opus: The New Science. The book was as revolutionary and controversial as its author. Vico once joked that trouble would follow him to his grave. In the midst of his funeral proceedings, the colleges of his university argued vociferously about who should have the honor of bearing his coffin. A riot broke out, police dispersed the crowd, and Vico’s coffin was left sitting abandoned in the middle of the street.

Vico was the West’s first true historian of consciousness. He was also the first to see history as recurring cycles rather than a linear progression; and the first to argue that the First People were a very different kind of human than you or I. He took special issue with an attitude that’s still common today, what he dubbed: “the conceit of scholars” — i.e., the presumption that humans in the past perceived, thought, and emoted exactly as we do today.

“The first gentile peoples, by a demonstrated necessity of nature, were poets who spoke in poetic characters. This discovery, which is the master key of this Science, has cost us the persistent research of almost all our literary life, because with our civilized natures we cannot at all imagine and can understand only by great toil the poetic nature of these first men.” (Giambattista Vico, The New Science, 1725 CE, emphasis mine.)

So who were these First People? According to Vico they were impassioned poets, rather than the “wise philosophers” we today like to think they were. In other words: their consciousness was more centered in emotion than in intellect. In addition: “They were, so to speak, all body.” Or in other words: the First People were “not in the least abstract, refined, or spiritualized, because they were entirely immersed in the senses, buffeted by the passions, buried in the body.”

When Vico was penning The New Science, the term ‘consciousness’ was only beginning to take on its modern meaning. So even though consciousness was exactly what he was talking about, Vico didn’t routinely use the term. Nonetheless his starting point is still the same for us today. In both cases, the foundation of human consciousness is sensory experience. Surely the First People’s brains would have worked with exactly the same sensory inputs as ours do today. So why aren’t you and I as immersed in the sensory world as they? Here’s the anthropologist Edmund Carpenter’s insightful explanation…

“A remarkable change took place in the human condition about three thousand years ago with the rise of Euclidian space, three dimensional perspective, and above all the phonetic alphabet. Each of these inventions favored the eye at the expense of all other senses. The value accorded the eye destroyed the harmonic orchestration of the senses and led to an emphasis upon the individual experience of the individual sense, especially the sense of sight. Where other senses were employed, it was with the bias of the eye.” (Edmund Carpenter, They Became What They Beheld, 1970, emphasis mine.)

3000 years ago was precisely when the trend towards patriarchal dominance was gaining serious momentum. So the re-organization of sensory interplay to favor visual dominance — a phenomenon Carpenter elsewhere terms: “synchronization” — must have accompanied and supported the emerging patriarchal agenda. One strong possibility is that synchronization of the senses may have increased the ability to focus, and the overall functional efficiency of those with access to the cultural developments Carpenter is referring to. And it was the men this time who seized the moment, and took control of the access.

In stark contrast, during the earlier cycle of matriarchal organization, human sensory input had been what Carpenter terms: “harmonically orchestrated,” meaning: all five senses contributed equally to a balanced symphony of information. The closest proximation we moderns have to this radically different manner of being in-the-world — a manner that by nature would have been less focused and more diffused — is a rather rare condition called synesthesia. Some individuals experience it spontaneously. And its not an uncommon experience under the influence of psychedelics…

Synesthesia is a neurological condition in which stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway (for example, hearing) leads to automatic, involuntary experiences in a second sensory or cognitive pathway (such as vision). Simply put, when one sense is activated, another unrelated sense is activated at the same time. This may, for instance, take the form of hearing music and simultaneously sensing the sound as swirls or patterns of color. (www.psychologytoday.com)

“All body” in Vico’s turn of phrase not only prioritizes sensory input, it also implies no mind — at least not what you and I understand by that term. Fully immersed in their orchestrated senses, and buried in their bodies, the First People’s consciousness was largely an expression of the reptilian instinctual (R-Complex) and paleo-mammalian emotional centers of the brain. This despite the fact that, according to neuroscience, their neocortexes — the thought and higher-function area of their brains — were probably as fully developed as ours. So given such a disproportional foundation, what could the terms ‘mind’ and ‘thought’ possibly have meant for them?

An important part of the answer lies in the work of the animal behaviorist Temple Grandin. Remember: the First People were still very developmentally close to their animal origins; and according to Grandin, animals think in sensory impressions (visual images, sounds, touches, smells, and tastes) and by making sensory-based associations.

Furthermore Grandin stresses that these associations are never established through abstract mentation; but through immediate, place-specific, personal experience. Every dog-parent can see that their dog thinks and makes choices. Do I want the toy or the treat? But canine thinking isn’t reasoned thought. It’s emotive, instinctual, concrete, and pragmatic.

Further support for this insight into the First People’s psychology comes from the philologist Bruno Snell, who in The Discovery Of The Mind (2011) tells us that his linguistic analyses of the 8th century BCE Iliad and Odyssey found no verbs referring to the generalized function of sight. Neither did he find any indication whatsoever of the kind of abstract, language-mediated conceptualizations that habitually populate our modern thought processes. What he did find was verbs and phrases that described specific and concrete modes of seeing — for example: “the stare of the snake.”

The anthropologist Robert Lawlor came to the same conclusion based on fieldwork in the Australian bush. “In spite of this linguistic power to distinguish each aspect and each individual plant, tree, or animal, Aboriginal languages have no words for abstract, generalized categories such as tree, plant, or animal.” (Robert Lawlor, Voices Of The First Day, 1991, emphasis mine.) And why are Snell’s and Lawlor’s discoveries significant? Because as Snell concludes: “If they had no word for it, it follows that as far as they were concerned it did not exist.”

In an earlier section I pointed out that a speaker of traditional Tz'utujil Mayan can only say ‘I am’ by naming who or what I belong to or am at-one with. Wouldn’t this suggest that in the consciousness of the First People the individualized sense of ‘I’, that you and I assume is a universal human experience, also didn’t exist?

This possibility alone might help explain the greatest disparity of all between the First People’s at-one psychology and ours. The matrix of their sensory-based, concrete thinking wasn’t the individual, but the community (i.e., com [with] + unity [oneness]). In other words: think ‘hive mind’, but in its highest possibility rather than the negative ‘group think’ connotation individualistic Westerners commonly associate with the term. Fact is, the personally constructed, carefully cultivated, private point-of-view, which is the psychological cornerstone of our modern experience of individuality, didn’t begin to emerge until the latter half of the 1st millennium BCE.

Clearly the First People were unique beings with singular capabilities and talents. However their identities weren’t based on these distinguishing qualities, but on family, clan, and totemic relationships. Once again: it’s likely that such a communal psychology is a legacy of their lingering proximity to the Animal At-one-ment. Orcas, for instance, who live in extended family groupings, appear to display a sense of ‘self’ that’s diffused throughout the entire family.

The corollary to this is that the First People were neither self-aware, nor self-conscious, in the way those terms are understood today. According to Snell, the Homeric Greeks neither experienced their own bodies as integrated units, nor themselves as the source of their own decisions. Instead they attributed all acts of volition to the agency of gods and spirits. Similarly, in a personal communication, Michael Michailidis wrote…

“The ancient understanding of nature reveals a consciousness that did not presuppose objective space and time. For the ancient Greeks, things did not move through a uniform grid that we understand as objective space but rather came in and out of existence like flickering lights, as potencies where realized into actualities and faded back into potencies.”

I find his characterization of ancient Greek consciousness of special interest because it’s almost exactly the way the linguist Benjamin Whorf describes the Hopi world-view. So taking all that I’ve presented in this section into consideration, it seems to me that we’re forced to come to three basic conclusions…

First: that the term ‘at-one-ment’, when used to describe the First People’s manner of being human-in-the-world, means exactly what it says.

Second: if people today can think more generally and abstractly about a world the First People only thought about concretely, then in the time between them and us the meaning of the word ‘think’ has significantly changed. And if what it means ‘to think’ has changed, then so too has the meaning of the term ‘consciousness’.

And third: if the meaning of consciousness has changed dramatically in the past, what’s to stop it from happening again in the future? What if it’s already happening right now, in our 21st-century lives?

THE BEAR MOTHER

Even though we couldn’t ask for a better characterization of the At-one-ment, Praetextatus’ claim that the Eleusinian Mysteria “hold the whole human race together” may seem a bit over the top. This, after all, isn’t exactly a modest claim! But remember: it’s coming from a high-ranking initiate of Eleusis, not some casual observer. So what exactly is Praetextatus trying to tell the sitting Emperor of Rome?

He could be alluding to the fact that people from all across the Roman Empire travel to Eleusis each September to take part in the Greater Mysteries, the culminating event of the Greek ceremonial year. He could also be talking about the archetypal experience of death and rebirth, symbolized by Persephone’s cyclical descent to the Land of the Dead and ascent to the Land of the Living. This mythic backdrop unites the inner circle of initiates and the outer circle of public celebrants in one sacred, mutually beneficial rite-of-passage.

But he might also be hinting at the deep personal healing, and renewed social cohesion, enabled by the At-one-ment-bolstering kykeon — the famed potion imbibed by both initiates and celebrants on the final day of the rite.

Based on a formula found in The Homeric Hymn To Demeter (7th century BCE), the kykeon was essentially an herbal tea consisting of pennyroyal brewed with a generous portion of fermented barley water. Pennyroyal is considered dangerous by Western standards; but it seems that participants in the Mysteria had a different experience. Revealing details of the rite was punishable by death; so the Hymn’s formula has to be at best incomplete. What many insiders did in effect get away with saying, and not pay with their lives, was that the culminating night rocked their souls. It may well have been an herbal brew; but it seems unavoidable to assume that one of its main ingredients had to have been a powerful psychedelic.

This possibility was first suggested in the 1950’s by the chemist Albert Hofmann, the synthesizer of LSD. Then years later Hofmann, the mycologist Gordon Wasson, and the Greek scholar Carl A. P. Ruck further developed the idea in The Road To Eleusis (2008). One strong possibility was a psycho-active ergot that grows on barely — one of Demeter’s two gifts to the ancient Greeks, and their staple grain.

One thing psychedelics do quite well is dissolve boundaries — not only the ones that separate humans one from another, but also the ontological boundary between humans and the Goddess. All-become-one then through the agency of the brew as the rite draws to its conclusion on a night that the historian of religion Walter F. Otto once compared to “the terrible festival of the deathbed.” A night when the graves of the dead were said to open, and the spirits of the ancestors issued forth to join with the living in remembering their at-one-ment with each other, The Mother, and The Maiden.

Demeter’s association with Greece’s staple grain, and her motherly concern for the fruitful living Earth, earned her the name: ‘Barley Mother’. However as Paul Shepard and Barry Sanders point out, the words 'barley' and 'bear' share a common etymology. So Demeter's name could also be understood to mean: 'Bear Mother', or better still: 'Grain of the Bear Mother'.

“The bear is thus also identified with spiritual well-being and with physical health and healing. Not only is it the animal of beginnings, but also of re-beginnings — of recovery from spiritual malaise and physical illness and, metaphorically, revival from death.” (Paul Shepard and Barry Sanders, The Sacred Paw: The Bear in Nature, Myth, and Literature, 1992.)

Demeter’s totemic at-one-ment with the bear is not only aligned with the Eleusinian rite’s core theme of death and rebirth, it also hints at the Mother’s esoteric role as patroness of Greece's most primordial spiritual lineage. Because as Shepard and Sanders go on to note: "The occupation to which the bear becomes an appendage is shamanism.”

O HOLY NIGHT

Now imagine this…

You and I are joining a large crowd gathering in the center of Athens. It’s a clear, warm September morning in 803 BCE. Looking around, we can see that the city itself is still youthful. The Literacy Revolution, in the form of the phonetic alphabet, has only just arrived, brought to the city’s bustling seaport by Phoenician traders. A coalition of four tribes is in control of the city. They’re intent on uniting the whole surrounding region into a single polity, including the agricultural community of Eleusis, 22 km to our west.

Eleusis, as you know, is important to Athenians because it houses a shrine dedicated to the Bear Mother, Demeter. All across the northern hemisphere, the bear’s annual cycle of hibernation has won this impressive animal a place in shamanist culture as medicine-keeper of the death/birth cycle. The Celts venerated Dea Artio, the Bear Goddess, who was specifically associated with childbirth, as our phrase ‘to bear children’ continues to give testimony. So it may not be a surprise to learn that the name Eleusis means: ‘place of birth’.

Suddenly the crowd is beginning to move, and stretching into one long line heading west. This procession follows a winding road along the sea. As we cross a bridge spanning a small river, each of us is offered a cup containing a strong-smelling brew. The bridge, we’re told, is a portal to the Spirit-world; and imbibing the potion is the price of admission.

All morning we walk, animated and emotional. Our senses are noticeably more acute, and the social bonding more accentuated. We all have become part of something much bigger; and I’m positive that Demeter and Persephone are walking with us. The early Greeks who pioneered this rite understood that the stresses of daily life gradually erode the experience of at-one-ment. That’s why they created a way to periodically renew it.

By midday we’re snaking our way up and across a mountain pass. On the far side, a huge plain spreads out below us. Vast fields of golden barley shine in the late summer sun, and ripple in the early autumn wind. As we descend into this undulating golden sea, we see our destination in the distance, sitting right at the heart of all this incredible beauty.

The sun sets before us. In response we light thousands of torches, and the entire procession turns into an earthly reflection of the Milky Way. See this evokes powerful emotions. Tears are streaming down everybody’s cheeks. Then we finally arrive at the shrine, still bathing in the kykeon’s warm glow, at-one and lit up like the stars.

The crowd fills and then spills beyond the large open space around the Telesterion, the temple of the Great Mother, Demeter. The building itself is an evolution of the ceremonial cave; and visitors describe it as a forest of pillars. Bonfires are lit and music fills the cool evening air as people begin to sing and dance their way through this longest and holiest of nights, when the spirits of the ancestors are said to return to pay their respects to the Goddess and her beloved daughter.

At-one with our Mother, we too know that once again it’s time for her beloved daughter Persephone to return to her husband in the Land of the Dead. Her sorrow is ours as well — and even more so for the select group of initiates, apprentices to and would-be servants of the rite, who we now see being led through the cheering crowd and into the Telesterion.

This is the tenth night of their fast, and the culmination of one full year of rigorous preparation. Tonight, the kykeon will help them experience what you and I may only come to know at the moment of our deaths – the final at-one-ment — to which the Mysteria are so often compared.

The Greeks call these walking dead: mystai — from whence comes our word ‘mystic’. Both derive from the verb myesis, meaning: 'to close one’s eyes'. That’s why the mystai are so often portrayed In frescoes with their heads draped in scarves. On this culminating night, at the apex of the ritual, and if the goddesses are willing, they will 'behold the vision' (epopteia), and become ‘vision-holders’ (epoptes).

And as the doors of the Telesterion close behind the mystai, you and I are left with the poet Pindar’s discreet hint regarding the experience that awaits them: "Happy is he who, having seen these rites, goes below the hollow earth; for he knows the end of life and he knows its god-sent beginning." (Quoted in Karl Kerenyi & Ralph Manheim, Eleusis: Archetypal Image of Mother and Daughter, 1991)

“SUPPOSING TRUTH IS A WOMAN — WHAT THEN?”

These words from the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900 CE) certainly apply far more to our evolving situation today than they did to the 19th century when the patriarchy was still unquestioningly entrenched. They also would have been far more applicable to the situation of the pre-classical Greeks.

As a people, the Greeks were the result of a confluence of two diverse cultural streams. One consisted of peaceful indigenous agriculturalists who revered the Goddess; and the other of bellicose equestrian invaders from the Caucasus who worshiped a sky-god. As different as these two groups were, they had one thing in common. Both were structurally 'shamanist', meaning: organized around the principles and practices of shamanism.

In Shamanism: The Neural Ecology of Healing and Consciousness (2000), the anthropologist Michael Winkelman argues that the world-wide distribution of this old, old practice is less a consequence of cultural diffusion, and more the result of its being: “a universal biological adaptation that enhances the evolutionary fitness of the species.” We tend to remember the patriarchal Greeks as paragons of rationality. What we don’t remember, because it’s not part of the patriarchal model of Greek history, is that the matriarchs who preceded the patriarchal rationalists were evolutionarily-fit shamanists.

With roots deep in both the practice of shamanism and the Neolithic Revolution, the Greeks were naturally attentive to the annual vegetation cycle. They explained the workings of this life-sustaining cycle with the story of The Maiden & The Mother.

Cycles are circles in time. Each has two phases: waxing (increase) and waning (decrease). Sometimes both phases are manifest in a single process, such as in the life-cycle of a plant. And sometimes cycles entangle two polarities in a perpetual revolving dance, for example: day and night, summer and winter, or matriarchy and patriarchy. And when a major cycle — like the matriarchal one from which the dream of Demeter and Persephone first emerged — is coming to an end, mightn’t one expect the collective psyche of a shamanist culture to engender a common dream to alert those affected and help them make the necessary adjustments so as to continue to be evolutionarily fit?

In the mid-1920’s a grave was discovered at an archaeological site in the Czech Republic named Dolni Vestonice. The burial was estimated to have taken place some 26,000 years ago. Interred paraphernalia identified the deceased as a shaman. What was most surprising, however, was that the remains were those of a 40 year-old woman. This was a game-changer, because it flew in the face of the long-standing patriarchal assumption that shamanism was exclusively a male prerogative.

Since then, the now well-established fact that everywhere First Shaman was a woman has garnered more support. For example: the archaeologist Christopher Powell — who has done extensive fieldwork at Palenque in Chiapas, Mexico — once told me that when the Maya depicted altered states, it was always the queens who were shown receiving the visions, and never the kings. So why then is a male by the name of Melampus — better known as “Black Foot” — credited with being Greece’s First Shaman?

For the same reason that few women in Greek history are even remembered. As we’ve already seen, women in patriarchal Greece were effectively the property of males. Still today, an unconscious patriarchal bias has continued to infect successive generations of Greek scholars — both male and female. Our current cycle of patriarchy first got started around 7000 BCE, but didn’t begin to achieve full dominance until after 3000 BCE. That’s when the matriarchal roots of shamanism were erased, and women in general reduced to chattel.

Research suggests that in Neolithic societies (12,000-4500 BCE), women held a far more equitable status. This was recently re-confirmed by the funerary treatment given a female infant some 10,000 years ago, suggesting that even the youngest females were recognized as full persons. The most profound work to date on the pre-historic matriarchal cycle was done by the controversial archaeologist and anthropologist Marija Gimbutas. In her view, the First People were by nature matrifocal, egalitarian, peaceful, and Goddess-aligned.

During the 8th millennium BCE, in the region Gimbutas terms “Old Europe” — which includes Greece — the descendants of the First People were living in large dwellings in small artistically-sophisticated towns, sustained by agricultural environs, and interconnected by established trade routes.

By the 3rd millennium BCE, the Goddess Cultures of Old Europe were in rapid decline. By 500 BCE, the remnants of the matriarchal At-one-ment were being pushed to the margins by an unprecedented new form of consciousness strategically co-opted by the patriarchy, and which is the topic of Part 2 of this essay.

By 500 CE, the emerging centers of Western political power and commerce were fully committed to the new form and the new reality. From then on, humans who were at-one, instinctual, emotional, poetic, communal, buried in the body, immersed in the senses, unself-conscious, of no-mind, imaginative, spirited, animist, shamanist, ritualistic, and Goddess-conscious were becoming increasingly rare. And then one day, except for the occasional surviving indigenous enclave or marginalized remnant, they were gone.

THE GREEK PHILOSOPHER/SHAMANS

The women shamans may have been forgotten; but the practices they perfected over thousands of years remained a powerful, even if somewhat hidden, force in the patriarchal takeover of Greek culture. Pythagoras (c. 571-495 BCE), for example, required that his students engage in a disciplined regime of yoga-like practices, passed down from the shamanic tradition, as part of their philosophical training. In The Greeks and the Irrational (2004), E.R. Dodds recounts how a demoralized Plato, angry and bereft at his teacher Socrates’ senseless execution, didn’t turn to his beloved philosophy for healing, but to these same Pythagorean praxes.

When the outcome of any matter was in doubt, Socrates (c.469-399 BCE) was known to recommend another traditional shamanic praxis: divination. Oracles like those at Delphi and Dodona gave broad cultural sanction to expanded states of consciousness pioneered in the camps of indigenous shamans. Temples of healing dedicated to the God Aesclepius — like those at Epidauros and on the Isle of Kos — were popular pilgrimage destinations well into the Hellenistic Period (323 BCE — 31 BCE). Cures were based on information obtained in dream-states, often induced with soporific medicines such as opium.

The treasured pinnacle of this deep shamanist undercurrent, however, was the second gift of the Bear Mother: the Mysteria. And in the context of shamanist society, the use of ‘entheagenic’ agents (literally: 'becoming the Goddess within') would have been quite natural. However, as essential as such sacraments may have been in facilitating the desired experience, their role was primarily a means to an end. This end, which is the ‘raison d’être’ of all shamanic practice, is a re-unification of any discordant or separative tendencies within the individual and the community. In other words: restoring both to their original, at-one state.

The main ingredient in the kykeon was barley. So whatever else may have been married to this grain to enable the shrine’s transcendental mission, could the Barley Mother — the Bear Mother — possibly have bequeathed humanity a more precious gift than a path and a practice that teaches humans how to live at-one with Her, with nature, and with each other? And now, the worldly fate of this extraordinary gift is about to be decided.

THE CONCEIT OF SCHOLARS

When we last saw Praetextatus, he was boldly and perhaps somewhat foolishly telling the sitting Emperor of Rome that his decree outlawing Greece’s nocturnal festivals was a really bad idea. A high ranking initiate of Eleusis, Praetextatus still holds the At-one-ment close. He may not understand the Mysteria as such, but they’re increasingly becoming a time-capsule of sorts, a miniaturized version of the old consciousness being passed forward in time to an increasingly disinterested Late Antiquity.

As a Christian, Valentinian’s decision determining the pagan Mysteria’s fate is purely a matter of political exigency. So it’s to everyone’s surprise, especially Praetextatus’, when the Emperor decides to heed his trusted advisor’s wise counsel and rescind his controversial decree. As you might expect, the Greek people are ecstatic. However, just as Greg Kinear's character in the film Ghost Town barely escapes being hit by an air conditioner falling from the window of a high-rise apartment, only to step off the curb and be killed by a bus, Eleusis' stay of execution is only temporary.

Just three short decades later, on a moonless night in 396 CE and on the order of the then-emperor Arcadius, an allied force of Christianized Roman troops and pagan Visigoth tribesmen overrun Greece’s last surviving Goddess-complex and reduce it to rubble. How could this rape not have been the preeminent insult prophesied in the dream of The Maiden & Her Mother? Whether I’m right about this or not, you might think that this is how the story ends; and in one totally obvious way, it is.

But in another it’s not. Because what happens next is really what you and I have come all this way back in time to try and understand. If the whims of zealous Christian emperors, and the cruel barbarism of ill-intentioned invaders weren't enough, Eleusis, the last surviving large-scale social institution of the Greek At-one-ment, is fated to suffer a third and final blow. Razed complexes can be rebuilt, and traumatized traditions healed. But what happens when the form of consciousness that underpins and sustains your very existence simply goes away?

In the centuries following the violent desecration, the Eleusinian rite becomes a subject of interest for Christian commentators and historians alike. Problem is: they just can’t wrap their heads around it, because the form of consciousness they’re now in-habiting is too structurally different from the one they’re trying to understand. As a consequence, they begin to make the mistake that Vico was talking about, and that we’re still perpetuating to this day: the presumption that humans past perceived, thought, and emoted exactly as modern humans do. In other words: they unwittingly fall victim to the ‘conceit of scholars’.

Essentially what these post-At-one-ment scholars and commentators are doing is projecting the individualistic form of consciousness their literacy-based European educations have conditioned them to embody onto the pre-individualistic Greek past. But all the exacting analysis in the world can’t possibly help them comprehend an experience that the at-one Greeks said was ‘arreton’ — ‘beyond the capacity of words to convey’.